Beyond the Book: Microfilm

Ann Lindsey, The University of Chicago Library

William Schlaack, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

This section of the Beyond the Book series looks at best practices for the care and handling of modern and contemporary microfilm. What is applicable to each microfilm base can be said for motion picture film base as well.

While microfilm has its origins with French photographer and inventor René Dagron’s first patent for the technology in 1859, microfilm only seriously caught on at a large-scale in the United States starting in 1935 when Kodak made use of 35mm film to record copies of The New York Times. During this time many microfilms were created using nitrate film stock (see below: A Note on Nitrate Film) with often disastrous results to both collections and people. For a fascinating look into nitrate motion picture film – its rise, fall, and conservation efforts, see the 2016 documentary Dawson City: Frozen Time. After World War II libraries and archives in the United States started using microfilm at scale to preserve documents and government records. Despite this advent of microfilming for preservation occurring during the time of acetate film, many collections still have holdings on nitrate base. Special care should be taken to identify and isolate these reels. From the mid-1920s through the early 1980s most microfilms were made using an acetate base. Acetate is susceptible to vinegar syndrome, which produces a tell-tale vinegar scent, along with causing the acetate to shrink and result in a roll that is difficult to unwind and deterioration of the acetate film base. This film should also be housed in isolation and monitored regularly (e.g. with A-D Strips). Ideally, planning should be undertaken to reformat all non-polyester based microfilm, as nitrate and acetate are subject to inherent vices that can render content unusable. Since the 1980s preservation microfilming utilizes silver-gelatin black-and-white images on polyester based microfilm as this is an inert material with a life expectancy of 500 or more years, assuming proper storage conditions.

Preservation Microfilm

Preservation microfilm is comprised of three generations:

- 1st generation (“camera masters” or " camera negatives" or “master negatives”)

- 2nd generation (“printing negatives” or “print masters”)

- 3rd generation (“service copies”)

Each of these has unique qualities but what is important to note is that only service copies should be handled by patrons, while other generations require careful use so as not to scratch the delicate emulsion.

Photo Credit: William Schlaack

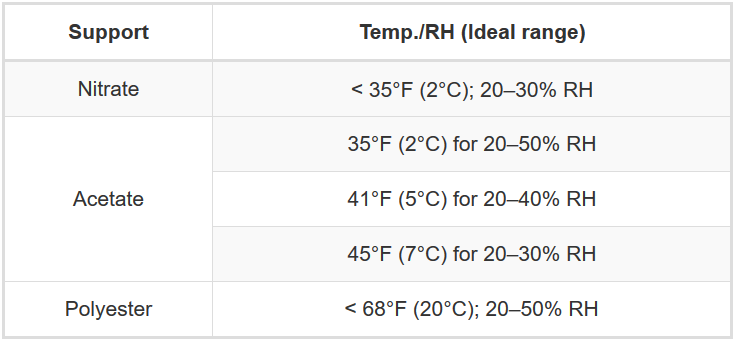

Best storage practices are governed by key American National Standard for Imaging Media standards (ANSI/NAPM IT9.11-1993 and ANSI IT9.2-1991). Essentially 1st and 2nd generations should be stored off-site in two separate locations if possible, while service copies should remain on-site for patron use. Even so, service copies should be kept in drawers that minimize exposure to light, and away from sources of air impurities. Housing units should be made of a noncombustible, noncorrodible material such as anodized aluminum or steel with nonplasticized lacquer coating. Films themselves should be stored individually on inert plastic cores, tied using a paper tag secured with a string and button tie (never use a rubber band), enclosed in buffered or neutral lignin-free boxes that pass the Photographic Activity Test. Cool storage (i.e. <50F) is considered best practice for film storage. However, given that many institutions do not have cool storage facilities, the following chart from the University of Illinois Preservation Self-Assessment Program is a great reference:

Chart credit: University of IllinoisPreservation Self-Assessment Program

Keeping in mind that a +/-5 degree or +/-5 % RH fluctuation is allowable.

Recommended Introductory Resources for Microfilm Care and Handing

Fox, Lisa L., ed. Preservation Microfilming: A Guide for Librarians and Archivists, 2nd ed. Chicago: American Library Association, 1996.

One of the best resources for the topic. This book is invaluable for administrators and preservation staff looking to build, develop, and maintain their microfilming programs. Special attention is given to selection of materials, production planning and preparation, as well as standards and practices. The appendices are especially essential as they provide the reader with examples of required microfilming targets and sample collation forms.

Northeast Document Conservation Center. 6.1 Microfilm and Microfiche.

An excellent overview of various aspects of microfilm and microfiche history, identification, and preservation. Includes sections on equipment, disaster planning, and digital conversion. Invaluable and updated with regularity.

Reilly, James. IPI Storage Guide for Acetate Film. Rochester, NY: Image Permanence Institute, 1993.

The Image Permanence Institute is at the forefront of many areas of preservation research, one of them being their studies of acetate film. This article goes into detail as to the science behind acetate and steps you can do to monitor acetate deterioration. Despite the depth the article remains easy-to-read.

University of Illinois, Preservation Self-Assessment Program. Collection ID Guide for Microforms.

This resource lists best practices for various types of microformats ranging from microfiche to aperture cards. Features photographic examples, definitions, descriptions, and information as to best storage environments for film types. PSAP also features an extensive bibliography of information regarding microforms (among many other formats).

A Note on Nitrate Film

The fact that nitrate film is a dangerous substance is fairly well known. Nitrate film is extremely flammable. It produces its own oxygen, therefore burns explosively, and is nearly impossible to extinguish once ignited. It has been known under rare circumstances to spontaneously combust at 100F. If that weren’t enough, as it breaks down it produces nitric acid that volatilizes into the air and can speed the decomposition of other materials stored near it. It is considered a hazardous material and needs to be stored in proper conditions and if necessary, disposed of properly. It was in production until the 1950s when it began to be phased out. Nitrate film is sometimes marked by the manufacturer near the edges of the film stock. If there is any question, it should be identified by a trained professional. The safest way of dealing with nitrate film is to reformat it and dispose of the original. Other possibilities are cold storage in a facility with walls thick enough to withstand any accidental ignition. Decisions regarding nitrate film should never be taken lightly.

This short video shows how easily nitrate film burns. Photo/Gif Credit: William Schlaack

There are several good sources of information about nitrate film, including Kodak, the National Park Service, the Library of Congress, and the American Institute for Conservation’s Conservation OnLine (AIC).

- Kodak: Storage and Handling of Processed Nitrate Film

- National Park Service: Disposal of Cellulose Nitrate Film

- Library of Congress: Care, Handling, and Storage of Motion Picture Film

- AIC’s CoOL:

The National Fire Protections Agency (NFPA) and the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) routinely update their standards for storage and handling of nitrate film:

- NFPA: Standard for the Storage and Handling of Cellulose Nitrate Film

- ANSI: Storing and Handling Cellulose Nitrate Film With NFPA 40

Patti Gibbons, Collection Manager in the Special Collections Research Center at the University of Chicago, shared the experiences she had with nitrate film.

We don’t have too much film in the collection, but I did face an interesting challenge a few years back when I surveyed AV media looking for preservation concerns and opportunities to improve their care. During the survey, I identified a few reels of nitrate film that presented dangerous fire safety possibilities. I needed to identify a vendor who would reformat the film and selected a firm that was out of state. We decided to have the original nitrate film destroyed after the successful reformatting. Transporting the nitrate film to the vendor was an interesting project. I researched how to ship hazardous materials and needed to work with our fine art crate maker to build a fire-safe film crate/tote that met the FAA’s regulations. Then I needed to work with FedEx to schedule the shipment. There was a great deal of paperwork, and our shipment was rejected twice at the airport by inspectors because small details were listed incorrectly on the paperwork. On the third delivery attempt, I needed to call the inspector at the airport. He worked the overnight shift and I believe we spoke on the phone at 1:00 am. He accepted the paperwork and container and the shipment went through to the vendor for reformatting. For me, it was interesting to learn about the flight and safety requirements. I was impressed (surprised?) at how strict the inspector was with the paperwork. It was an interesting process. After that review, I also purchased a flammables cabinet in the event that we ever accession in more nitrate film or get archival items with similar issues needing a safe “holding area” before being fully integrated into our storage areas.

Return to Beyond the Book: Preserving your Non-Book Collections