Planning for Special Collections Exhibits — Interview with Marco Vinicio Valladares

An Interview with Marco Vinicio Valladares Perez, Exhibits Conservator at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

William Schlaack, Digital Reformatting Coordinator, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

For 2019-2020, the CARLI Preservation Committee is sharing a series of interviews with preservation managers, conservators, and other library specialists who graciously described their experiences on preservation and conservation topics of interest to CARLI libraries. This month, William Schlaack, Digital Reformatting Coordinator at the University of Illinois asked Marco Vinicio Valladares Perez, Exhibits Conservator at the University of Illinois, to share some of his experiences working with exhibits.

|

Interview with Marco Vinicio Valladares Perez on Planning for Special Collections Exhibits: |

| What is the Preservation role you play in your institution? Can you give us a summary? |

|

About two years ago, the Conservation Lab created the position of Visiting Exhibits Conservator, for which I was hired. This position was created to work in collaboration with the curators of the archives of the Rare Books and Manuscript Library (RBML) and the Illinois History and Lincoln Collections (IHLC). Our objective is to organize, plan, and implement exhibitions throughout the year. Each archive organizes three annual exhibitions in spring, summer, and fall. My responsibilities include: organizing a work schedule; evaluating books and documents that the curators would like to exhibit; deciding whether or not these books and documents are able to be exhibited due to their conservation state; deciding if they require conservation treatment, and implementing this treatment; designing exhibitions with the curators; creating cradles and raisers for exhibiting books and documents; installing and de-installing exhibits; building containers for storing books and documents; and researching conservation treatments. |

| What level of expertise do you feel you bring to creating exhibits and preserving the objects displayed? Can you share an interesting story about an exhibition you’ve done? |

|

I am from Ecuador, where I studied Conservation and Museum Studies. In Ecuador, these are important areas of study, because we have a long history of precolonial and postcolonial art. What is also interesting about studying conservation in Ecuador is that we learn conservation techniques for a wide variety of materials and objects. I learned how to conserve everything from oil paintings and wood frames, to paper documents, maps, and books, to sculptures, religious objects, and even buildings such as churches, convents, and monasteries. I also worked on conserving artwork and documents for the government and private collectors. This experience is the foundation of my work at the University of Illinois. Here at UIUC, the most recent exhibition we have created in RBML is called “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Conservation Treatments and Decision Making Through the Ages.” This exhibit is open to the public until December 20, 2019. This was an interesting exhibit to put together because it was the first time that a small group of us from the conservation lab were also curators, in charge of almost every step of the process, from conceptualizing the exhibit, to choosing the objects to display, to deciding how to display them. I really gained insight into the work of curation and how difficult it is. I have new respect for curators! We had to select books and documents within the RBML archive, which is home to over 600,000 volumes. We were literally walking through the archives—a space that contains over two miles of manuscript material—looking for books that would fit with our idea. We had to ask ourselves: What represents “good” conservation? What about “bad” conservation? What does that look like in a book from the fifteenth century? These were fun questions to ask and attempt to answer, from a curatorial and conservation point of view. |

| What interests you about your job? |

|

Working with books is one of the most important jobs I have had. This work involves maintaining and preserving human knowledge in the present and for the future of humanity. It is my way of contributing something good in the world. |

| How do you choose what to display? |

|

The curator is in charge of selecting the theme of the exhibition and conducting an initial selection of the books and documents to be displayed. After this first step, we work together to analyze the items and determine which will be displayed, which items require conservation treatment, and which must be replaced by facsimiles (replicas) due to their poor state of conservation. For example, we cannot display historic photographs because they are too light sensitive. Some old books and documents are too structurally damaged to be displayed, for example when the paper is damaged, or the spine is falling apart. In those cases, we take longer to conserve those objects, and we choose other objects for the exhibition that may have stronger paper, leather, sewing, spine, etc. |

| How does space relate to the exhibit? |

|

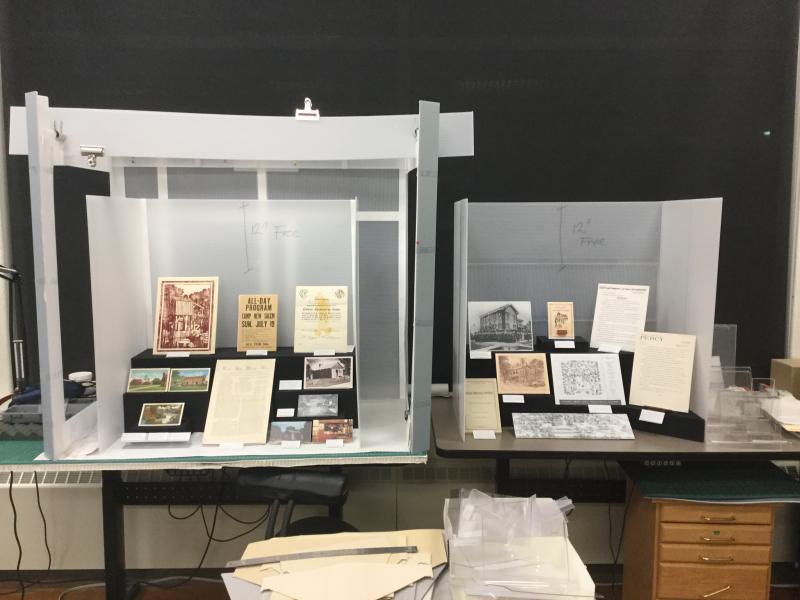

The space we are working with determines what the exhibit will look like. The size of the space determines how many objects we can display, the design and concept of the exhibition, how much time we need to plan, how many workers are needed to install, etc. Usually, larger spaces require a more complex planning process. In RBML, our exhibition space is 40 square meters (430 square feet), which is enough space for six cases. In IHLC, we have space for two cases. We always try to maximize the space we have in terms of the cases, the objects inside them, lighting, walls, etc. I try to be creative with each exhibition, so that each one is new and unique. I like the idea of incorporating colors, photographs, videos, and interactive objects into the exhibits, along with documents and books that are on display, in order to grab the public’s attention and provide a more interesting experience for them. |

| How do you want visitors to experience the exhibit? |

|

I would like visitors to enjoy the exhibits and learn something new in the process. I want them to leave the exhibit thinking, “That was cool!” |

| Have any of your exhibits been interactive? |

|

In the last exhibit we put on in RBML, “The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly: Conservation Treatments and Decision Making Through the Ages,” we used all the resources we could to make the exhibit as interactive as possible. The inaugural event included a talk by Chela Metzger, Head, Library Conservation Center, UCLA, and an important figure within the conservation field. We included various videos for the public to watch on our webpage, the exhibit itself included many photographs. We created a catalogue, which summarizes for the public what conservation is, what techniques we use, and a summary of the specific objects included in this particular exhibit. As part of the exhibition, we also included an interactive table with objects that the public could touch and experiment with. These were objects that conservators use in their everyday work, such as Japanese paper, leather, and parchment paper, as well as a magnifier that the public could use to see the fibers of these materials and to see how conservators are able to tell whether or not something is damaged and requires treatment. |

| Do you have a schedule for your exhibits? On average, how long are they on display? How far in advance do you schedule and plan exhibits? |

|

We have three exhibits a year—spring, summer, and fall—in both the RBML and the IHLC archives. The spring exhibits usually run from January-June; the summer exhibits usually run from June-September; and the fall exhibits usually run September-December. We need a year to plan exhibits in RBML. As soon as one exhibition is installed, we are immediately working on the next one. The spring and fall exhibits require the most time to prepare, because they include events such as an inaugural talk, workshops, the creation of catalogues, etc. On the other hand, IHLC exhibits are a little smaller, so they only require three to four months of preparation. |

| How do preservation practices figure into display? |

|

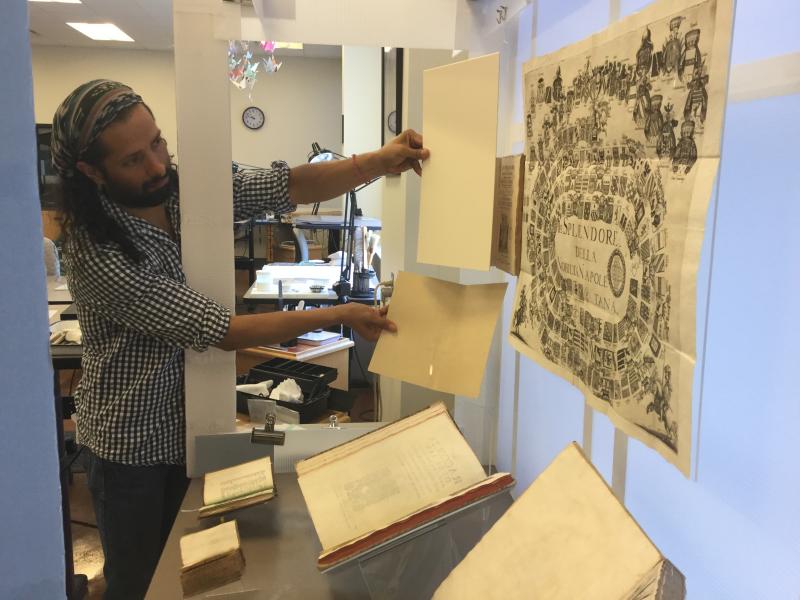

Conservation is fundamental to the preparation of exhibits. First, we have to determine if an object can be displayed or not due to its conservation state and the material out of which it is made. We have to monitor the humidity of the exhibition spaces, as well as the intensity of the lighting, to make sure neither the humidity nor the lighting will damage the objects. Then we have to build cradles, raisers, and other objects that will support the documents and books on display, making sure that these structures will protect the objects during the time they are on display. Before installing the exhibit, we conduct a pre-installation, during which we analyze the humidity, the physical stability of the structures, the stability of the objects, and the aesthetic design of each case. If necessary, we have to use silica gel to regulate the humidity of the cases, especially when we are displaying objects that are made out of parchment (unprocessed animal skins) which are sensitive to high levels of humidity. |

| Do you have any recommendations of suggestions for how others might learn more or keep up-to-date on exhibit work at UIUC? |

|

Both the Rare Book and Manuscript Library and the Illinois History and Lincoln Collections are located on the third floor of the Main Library on campus: 1408 W. Gregory Drive. RBML is located in room 346, while IHLC is located in room 322. These areas are open to the public Monday through Friday, 9am-5pm. |

| Thank you very much, Marco, for your extraordinary responses! |

Return to Preservation Interviews: Learning from our Collective Experiences, the homepage of the Preservation Committee's 2019-2020 Annual Project.